Interview with Aaron Carnes

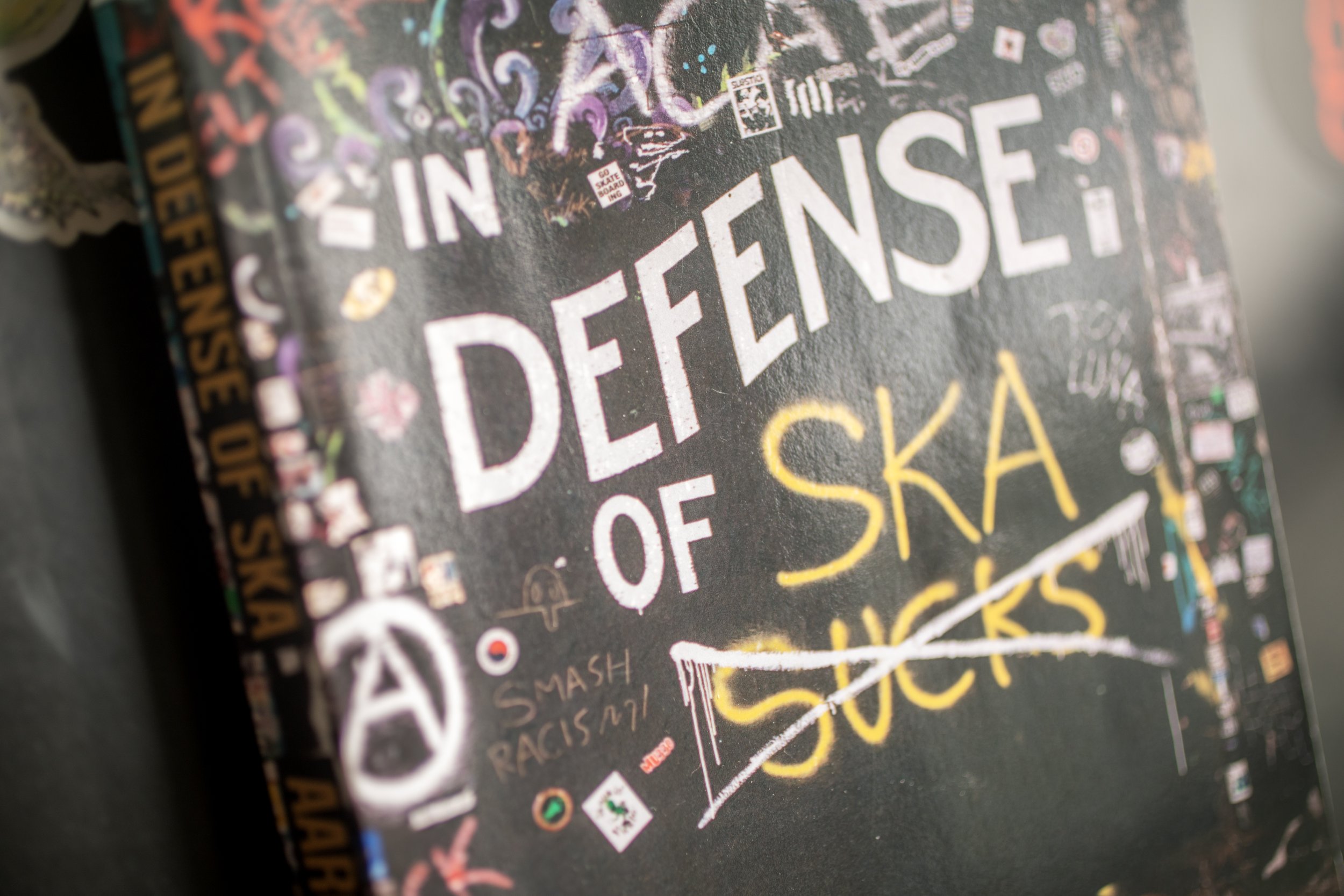

In Defense of Ska by Aaron Carnes is an entertaining take on the story of third-wave ska. It’s written with the wit and sarcasm indicative of the movement, and it’s being released in an expanded second edition by CLASH Books. Carnes takes us through his days as a roadie for Skankin’ Pickle, gives us historical tidbits about the various waves of ska, and provides a personal account of why this genre of music has had such a worldwide impact.

Tom Winchester: Stylistically, your book is somewhat of a memoir.

Aaron Carnes: It’s partially a memoir, but also a journalistic view of the scene. Having different perspectives on this topic, I think, it gives people a bigger sense of what was going on and why it mattered to people. It’s not just about what happened, but also why it was important to people.

TW: It was a movement that was driven by the fans.

AC: Because the 80s was kind of a no-man’s land for indie labels and indie touring, indie music was really difficult to do. But by the time we got to the 90s, you see the indie scene was a lot healthier. So, some of these bands were squeaking by. Either they were barely making enough of a living to not have to work, or they were able to do little part-time jobs here and there and make their band their living. I think it was because of indie networks like zines, indie labels, and touring.

You also had the MTV situation, and the major label situation, specifically with Nirvana and Green Day, where major labels saw the indie scene as the minor leagues. Like, ‘Here’s where we get our next act. Here’s where we see things kinda crackin’ right now.’ All of these things happening in the 90s created a unique dynamic unlike any other decade. And when it all blew up with Napster and downloading, part of why everyone viewed it as so devastating was because of how much money was flowing in the 90s, and how much opportunity there appeared to be for bands.

TW: In what ways do you think the third-wave ska movement appropriated themes of nihilism and irony from the grunge movement? Even the seemingly meaningless and silly band names appear to have something to do with nihilism.

AC: In some ways, grunge and ska were quite different. I always thought grunge bands took themselves a bit too seriously. I think what you’re tapping into is very Gen X. All of us who grew up in Gen X have a sense that, ‘Everything’s kinda bullshit.’ You see that idea in the seriousness of grunge and the silliness of ska. It’s the same message coming from people of the same generation but expressed differently.

Back in the 90s, everything felt very separated: ‘I like this, and I don’t like this.’ But now, it’s funny, because people are reflecting on the 90s as if it’s its own genre—it’s not a genre—but I think what people are picking up on is the general tone of the 90s. That peak Gen X attitude was all over it.

TW: I think Gen Z has a similar grunge-y nihilistic attitude because they were left with a world of leftovers. To me, the Gen Z identity, like that of Gen X, seems to be steeped in irony.

AC: Gen X is full of irony. If I can make a stereotype about my generation: we saw our parents, the hippie generation, who were full of purpose and were going to change the world, sell out to the corporate world…

TW: …the “Deadhead sticker on a Cadillac”...

AC: …We were full of irony, cynicism, and our outlook on life kind of came from that. I think you see it all over 90s culture.

TW: You make the point that the 2 Tone movement added punk to ska music, not the third wave.

AC: The third wave added pop-punk and hardcore, as well as the various sub-genres that punk had evolved into. I make this point a little better in the expanded, second edition: I think that if the momentum of punk bands like Green Day, The Offspring, and Rancid hadn’t happened, then we may not have seen a mainstream ska movement.

There’s been a discussion surrounding ska having a big moment since the 80s because it had been around with 2 Tone, but there was a lot of apprehension on the parts of the major labels in terms of people wanting to push it on those levels. I’m not sure they knew what to do with it, I don’t think they understood how to market it, and I don’t think they had a lot of faith that it would reach a larger audience. But once pop-punk showed itself to be a massive cultural force, I think it gave the radio stations, MTV, and major labels the map to say, ‘Well, this is how we can market this music to make it bigger. The bands who are incorporating pop-punk, those are the ones to accelerate.’ It could have been Hepcat or Fishbone, or all kinds of bands, but pop-punk made a lot of sense to MTV and major labels. So, those bands got pushed instead.

TW: I would argue that its affiliation with pop-punk is what killed ska. In terms of selling out, what Blink-182, Good Charlotte, and Sum 41 did to punk rock was so much more egregious than anything No Doubt or Reel Big Fish could be blamed for with ska. Moon was always my favorite label because it had a lot of ska-jazz.

AC: To some degree there were West Coast, East Coast, and Midwest sounds. The West Coast was rooted in punk more so, like Operation Ivy and bands who played at 924 Gilman Street in Berkeley, California. The East Coast definitely had a jazz component, which was led by Moon Records. The Midwest was pretty much anything goes, with Jump Up being the main label in that scene—but the Midwest tended to not be rooted in traditional ska.

Every city had a unique scene. You could say that California had a sound but there were differences between Northern and Southern California. With Northern California, Gilman loomed over the scene pretty largely in terms of its impact. Southern California had a sort of wacky sound, in Orange County, but it also had a vibrant—possibly the most vibrant in the country—traditional ska scene that was largely in Los Angeles. They were totally separate scenes.

TW: Operation Ivy was one of the turning points in ska with their blend of moonstomping with street-punk. But they’d broken up by the time their album was released. This influential band, to most of us, never existed.

AC: It’s hard to pinpoint a period of time when Operation Ivy’s influence really took root because most people outside of California were unaware of them when they broke up. They were not a big enough band to have reached a national audience; that came years later, in waves. The first wave was through the release of their album by Lookout Records, which they pressed on CD. Then, you had Green Day blowing up and shouting out Op Ivy, and playing Op Ivy’s song “Knowledge” on tour. And then you had Rancid blowing up, and their fans starting finding out they had a previous band. So, there were phases of Op Ivy’s influence.

You then got bands like Suicide Machines who were clearly from that vein. Yet, Dan Potthast from MU330 told me that he doesn’t consider Op Ivy to be one of his early influences because he hadn’t known about them until the band was well known. A band like Fishbone was much more influential to those early 90s bands because they’d been popular since the late 80s. Op Ivy was more of a gradual thing; you eventually learned about Op Ivy.

What I think was their most significant contribution to ska was that they sort of said, ‘You can be punk first and ska second, and still be ska.’ That’s really the defining characteristic that Operation Ivy brought to the ska scene in the 90s. They were kind of sloppy, the guitar tones were dissonant; they really embodied these punk elements first, and then they played ska. I think a lot of bands took away the idea that they could be punks who played ska.

TW: Do you have a specific memory of the turning point when ska became not cool? Was there a moment when you first realized the movement was over?

AC: In my observation, it started in ‘99, or so. I can’t point to a specific moment, but that’s when we saw it get looked down upon, and more so into the mid-2000s. I found an article from the New York Times that makes fun of Vampire Weekend’s second album because it had ska elements. There’s no way to phrase it any other way. They were just making fun of them because of it. That specific period was a low point for ska. There were some scenes that were pretty active, though, especially in the early 2000s. So, ska never really died. It had just left the mainstream at that point.

TW: With your discussion of Annette Funicello’s version of “Jamaica Ska,” I think it’s really supportive of your thesis to give an example of what a blatant sell-out song sounds like. By comparison to Reel Big Fish songs, for example, which were being ironic about selling out, the Funicello version of “Jamaica Ska” is a total industry product.

AC: The sell-out nature of the Anette Funicello version of “Jamaica Ska” is compounded by the fact that the original Byron Lee version, to some, is also seen as a sell-out song. I’ve talked to some people who have pretty heavy opinions about Byron Lee being somewhat of a culture vulture who came in and took the sound of the locals and brought it uptown. It’s a heated discussion. I have one Jamaican friend who has some pretty angry words for Byron Lee.

TW: Because of your connection to Skankin’ Pickle, I feel like you might say Asian Man, but would you agree that Mojo was the greatest label in the history of American ska?

AC: You could say Asian Man, but you could also say Hellcat. Hellcat had some pretty good records. There really aren’t any bad Hellcat ska records.

TW: Would you agree that The Slackers are probably the best American ska band?

AC: Yeah, The Slackers or Hepcat. If I were to give someone a ska record I’d give them Right On Time by Hepcat or The Question by The Slackers.